Could Ransomware Go Embedded?

For criminal hackers, ransomware has become increasingly popular. Ransomware locks a PC or encrypts its data and ask for a ransom to be paid to the hackers to unlock the PC or decrypt the data.

For criminal hackers, ransomware has become increasingly popular. Ransomware locks a PC or encrypts its data and ask for a ransom to be paid to the hackers to unlock the PC or decrypt the data.

To which extent are embedded systems vulnerable to similar attacks? How realistic is it that firmware update mechanisms are used by hackers to install foreign code? Although loading malicious code to deeply embedded systems might seem far-fetched, some of the Snowden documents have shown that this already happened to the firmware in disk drives. Also, the well-documented Jeep Cherokee attack in 2015 that allowed a remote operator to almost entirely remote control the vehicle shook the industry. A wake-up call?

The Challenges

For hackers, the challenging part is that even though there has been a development to use more off-the-shelf hardware reference designs and software, most Embedded Systems platforms are still different from each other. Different microcontrollers require different code, so that ransomware has to be tailor-made for a specific microcontroller. The bootloader mechanisms in place are also different which means hackers need to find exploits for every one they are trying to attack.

A hacker’s task would be to write an exploit that manages to replace the entire original code and includes an own, password-protected, bootloader. With payment of the ransom, the hacker would share details on how to use his bootloader. There would of course always be the risk that this feature was not tested well enough by the hacker and a restore was not possible at all. It can be assumed that far more effort would have gone into generating the exploit and replacement code than the unlocking and restoring procedure.

Note that many microcontrollers have a built-in on-chip bootloader that cannot be erased or disabled, so if such a bootloader is usable in a device, a device with ransomware could be re-programmed on-site by the manufacturer or a technician. However, that might still be impractical or expensive if, for example, a very large number of devices were affected and/or the devices were at very remote locations.

A theoretical Example

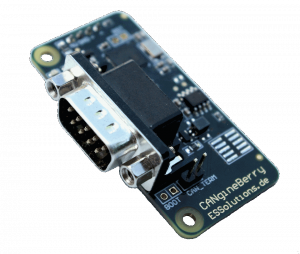

To pick a specific application example, let’s have a look at an elevator / lift system: It consists of multiple microcontroller systems that are interconnected for example by CAN or CANopen and let us further assume they also feature a CAN/CANopen based bootloader mechanism.

A hacker installing ransomware replacing the existing bootloader with their own would need to

- get access to the system (either physical by installing a sniffer or remotely through a hacked PC that is connected to the system)

- know which microcontrollers are used

- know how the CAN/CANopen bootloader mechanism works (with some CANopen profiles, some details about it are standardized)

This information might be stored on multiple PCs: with the manufacturers, distributors, technicians or operators of the system. If one or multiple of those get hacked, an attacker might have all this information readily available. Note that the risk of a rogue or disgruntled employee with inside knowledge is often underestimated. The information above will typically be accessible by many people.

With this information, a hacker would be able to generate and load his own ransomware loader replacing the original code in all devices, which would disable the system. Now buttons, displays and controls would all stop working and every affected device / microcontroller would require a restore of its original firmware. If the affected devices still have an on-chip bootloader and if it can be activated, then a technician could manually update all affected devices. For large elevator systems with 20 or more floors and multiple shafts this task alone could take days.

How likely is such an attack?

The sophistication level required for the attack described above is quite high. Not only does it require “traditional” hacker knowledge but also in-depth knowledge of embedded systems. At this time it might be unattractive to most hackers as there are possibly still many “easier” targets out there. However, with enough resources thrown at the task, a determined hacker group could achieve the tasks listed above.

What are possible counter measures?

The most basic pre-requisite for an attack as described here is the knowledge about the specific microcontroller and bootloader mechanism used. This information can be obtained by either monitoring/tracing the CAN/CANopen communication during the firmware update process or by access to a computer that has this information stored. Protecting these in the first place has the highest priority.

The designer has to make sure that the firmware update process is not easy to reengineer just by monitoring the CAN/CANopen communication of a firmware update procedure. Things that we can often learn just by monitoring a firmware reprogramming cycle:

- How is the bootloader activated? Often the activation happens through a specific read/write sequence.

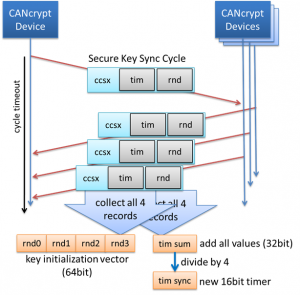

Counter measure: Only allow authorized partners to activate the bootloader, best by using encryption such as CANcrypt or at least a challenge/response mechanism that is not repetitive.

- What file format is used? “.hex” or binary versions of it can easily be recognized.

Counter measure: Use encryption or authentication methods to prohibit that “any” code can be loaded by your own bootloader.

- What CRC is used? Often a standard-CRC stored at end of the file or loadable memory.

Counter measure: If file format doesn’t use encryption, at least encrypt the CRC or better use a cryptographic hash function instead of a plain CRC.

These counter measures are fall-back safeguards to protect the system if a higher security level has failed before. A hacker should not get bootloader access to a deeply embedded system in the first place. Ensure that all remote-access options to the bootloader level are well-secured.

Deutsch

Deutsch English

English

Learn about our current product range for embedded systems

Learn about our current product range for embedded systems

Embedded Networking with CAN and CANopen. Your technology guide for implementing CANopen devices.

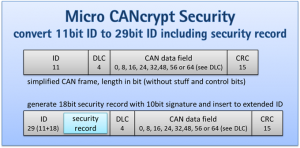

Embedded Networking with CAN and CANopen. Your technology guide for implementing CANopen devices. Implementing scalable CAN security. Authentication and encryption for higher layer protocols, CAN and CAN-FD

Implementing scalable CAN security. Authentication and encryption for higher layer protocols, CAN and CAN-FD